The following skills are necessary for creative thinking and discovery of the truth:

- poly-perspectivism;

- polymathy;

- understanding how the brain generates potential solutions to problems;

- recognition that observation is the best source of information;

- communication;

- recognition that authority has no monopoly on the truth;

- recognition that models and other simulations of reality are always flawed; and

- detective skills.

Poly-perspectivism was described in the previous article “Perspectivism and Poly-perspectivism”. In summary, no-one has the mental capacity to fully understand all aspects of a problem. Each of us is only capable of a partial understanding. This concept is known as perspectivism. It is possible, however, to expand and improve our understanding by interacting with others who have a different perspective. This does not, of course, necessarily mean accepting their perspective. Rather, it can reveal aspects of a problem that we had not previously thought of.

Polymathy. A polymath is someone whose knowledge spans a wide range of subjects. This enables them to see similarities between concepts in different fields of knowledge, even though they may be expressed in different language. This in turn, enables them to transfer innovations and discoveries from one field to another. Furthermore, it enables them to identify inconsistencies between theories in different fields. This article in The Conversation describes research by Robert and Michele Root-Bernstein of the University of Michigan. They have found that Nobel Prize winners are unusually likely to be creative polymaths. The article also gives examples of two such prizewinners.

When we work in specialist silos, we can construct theories that contradict those in other silos. Unfortunately, those contradictions can go unnoticed. So, a good method for discovering the truth is to aim for breadth of knowledge rather than depth. Try to understand the fundamental principles of several disciplines. These principles can then be combined to create theories. If the theories are inconsistent with one another or what we observe to be true, then some of the fundamental principles must be incorrect.

Understanding how the brain generates potential solutions to problems. This was described in a previous article entitled “The Creative Process and Decision Making”. In summary, we can follow a four-stage process that harnesses the ability of the unconscious mind to solve problems. Stage 1, known as saturation, comprises learning as much as we can about the relevant issue. Stage 2, known as incubation, involves resting the conscious mind and allowing the unconscious to process that information. This may involve taking a short break from our desk or PC, or it may involve one or more nights of good sleep. Stage 3, known as inspiration, occurs when the unconscious mind, without prompting, presents its potential solutions to our consciousness. It is the “aha!” or “Eureka!” moment. Finally, stage 4, known as verification, comprises consciously checking that the inspiration is correct. Unfortunately, the unconscious mind does not always get it right. So, some additional research and incubation may be necessary. Once we understand this process, we can consciously employ it to great advantage in our day-to-day efforts. It is why it is often wise not to make decisions precipitously, but rather to “sleep on them”, or think about them for a while.

Recognition that observation is the best source of information. Human senses have evolved to better enable us to survive and procreate. So, one would expect the information gained through them to be a reasonable representation of reality. On the other hand, information gained from others is not necessarily true. We can also construct theories that contradict observed reality. There are a multitude of reasons why theories may be wholly or partially false: simple error, assumptions learned from society, a wish to gain status and attention, a wish to deliberately mislead, and so on. Building theories upon theories without verifying them by observation can lead not only to the propagation of errors and falsehoods, but also to the amplification of them. It is for this reason that scientists carry out practical experiments to verify their theories, and the same should apply in our daily lives.

Communication. It is better to express complex ideas in simple language, rather than simple ideas in complex language. The former increases the likelihood that the idea will be understood. The latter is often mere pretentiousness, with the aim of gaining unwarranted status. Unfortunately, the latter can also hide simple concepts behind a cloak of mystique. Consider, for example, the words of one eminent professor commenting on the work of an eminent sociologist:

“Under the regime of self-referential systems, “self-regulation” changes sense from automatic control to autonomous self-constitution, and the polarity between open and closed systems is sublated by supplementary relation binding openness to the environment to the closure of system operations.”

These words can be translated into plain English, as follows:

“A self-referential system contains and uses a description of itself. It is, therefore, self-aware. The theory of self-referential systems states that they control their own processes, rather than working automatically. They also recognise a difference between relationships within themselves and relationships with their environment.”

I am sure that all self-aware human beings regard this statement as obvious once it is stripped of its jargon.

Recognition that authority has no monopoly on the truth. In life, we encounter individuals who have high social status because of their work in a particular field. We have a natural tendency to accept their theories as being true. This is known as “appeal to authority”. It is a logical fallacy which suggests that high status individuals have a monopoly on the truth. However, status can be carefully cultivated as a goal. Furthermore, a strong bond can develop between an individual’s status and the theory put forward by them. So, the theory becomes resistant to change, even in the face of contradictory evidence. Those who benefit by supporting the high-status individual are similarly bound to their theories. So, we should not automatically accept theories simply because they are propounded by someone of high status.

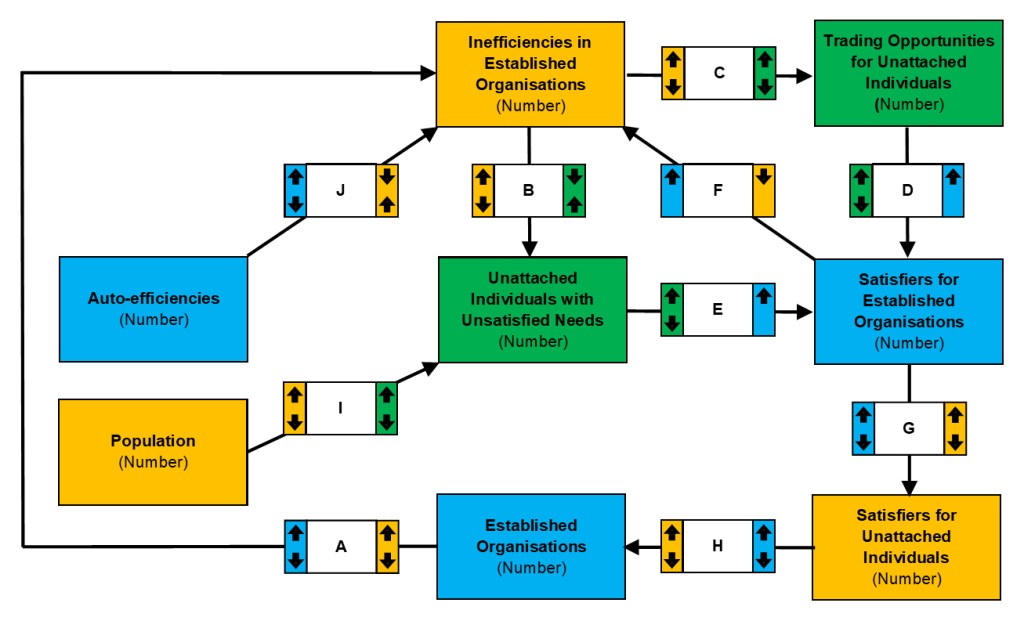

Recognition that models and other simulations of reality are always flawed. Because human cognition has evolved, it can be expected to be a reasonable representation of reality. However, its limitations mean that it must also be a simplification. We formalise our understanding using various models, for example, language, mathematics, diagrams, computer simulations, etc. Inevitably these models are also simplifications.

Models can be used, to a limited degree, to predict events. However, the prevailing view is that increasing their complexity by, for example, increasing the number of variables, does not necessarily increase the accuracy of their prediction. It is more effective to identify the most significant variables and keep the model relatively simple.

Detective Skills. To convict a criminal, the prosecution must convince the jury that the defendant had the motive, means, and opportunity to commit the crime. The motive is the reason to commit the crime, the means is the ability and necessary tools to do so, and the opportunity is the time and circumstances that make the crime possible. If any of the three are absent, then the defendant is not guilty.

The same is true of any act, criminal or otherwise, and so, theories about social causes and effects can be tested in the same way. For example, does a government have the motive, means, and opportunity to enact environmental legislation? It certainly has the means, and if the legislative programme permits, it has the opportunity. It is, therefore, the motive that is questionable and where attention needs to be focused.