Introduction

I will now use the principles of general systems theory to describe the nature of human society. Due to its length, I have split this article down into three posts, but if you would like to read it in one sitting a copy can be downloaded here https://rational-understanding.com/my-books#systems-model.

The model is generic and applies to human organisation at all scales. It can only be fully understood if this is borne in mind. Some of the terms used are borrowed from particular aspects of human organisation, such as international affairs. However, here they are used generically. Examples are also given from various branches of human organisation, but again the concept described can be applied generically.

The Structure of Society

Human society is a hierarchy of organisations. In this context, the word “organisations” has a general meaning which includes not only formal organisations, such as those found in business or government, but any group of people who work together for a common purpose. It also includes any individual person. The hierarchy typically comprises the following levels. Level 6 is the highest, and level 1 the lowest.

6. Global System

5. National Groupings

4. Nations

3. Sectors

2. Organisations

1. Individuals

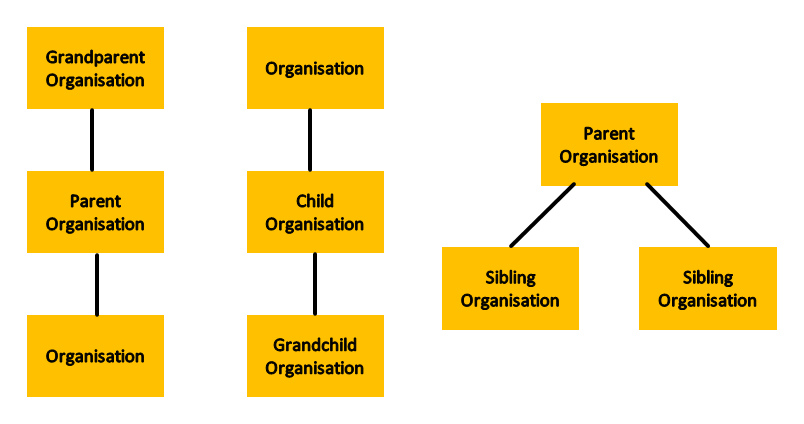

There is, of course, only one global system. However, the other levels each comprise several systems each of which is an organisation. Each organisation, except individual people, comprises several component sub-systems which are also organisations. Thus: the global system comprises several national groupings; each national grouping comprises several nations; each nation has several sectors; and so on. From the perspective of any organisation, the levels above it are its environment. If an organisation is a part of a more extensive organisation at a higher level, then the latter is referred to as a parent or grandparent organisation.

This structure is recursive, i.e., the same principles apply to organisations at every level. This helps to simplify what would otherwise be a very complex social structure.

Progressive Mechanisation & Centralisation

According the biologist, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, it is common for “progressive mechanisation” to occur in biological systems. That is a system whose components initially carry out all the functions of the organism begin to diversify and take on specific roles depending on their location within it. Thus, for example, an embryo initially comprises identical cells but, as it grows, they diversify to form organs, each with a different purpose.

On the other hand, “progressive centralisation” also occurs, i.e., controls such as the nervous system develop to direct the behaviour of those specialised organs, and co-ordinate their activity.

These processes, by specialising and co-ordinating the activities of the components, enable systems to behave in more complex ways than would otherwise be possible. The resulting behaviour is, of course, subject to natural selection and, thus, evolution.

Similar processes take place in social systems. For example, the members of a small tribe will all be capable of carrying out every function of the tribe. However, as it grows into a larger social group, individuals will begin to specialise, and a leader will emerge to organise their activities. Thus, one can expect people who live a relatively isolated and self-reliant rural life to be multi-skilled and individualistic in attitude. Those who live in cities, on the other hand, can be expected to be more specialised and collectivist in attitude.

Requisite Hierarchy

Every human organisation is a self-maintaining system, comprising inputs, processes, and outputs. It also has goals which act as motivators for its behaviour. In an individual human being, our motivators are the satisfaction of our needs, i.e., states that we are motivated to attain. We are also motivated to avoid negative states which I refer to as contra-needs. More generally however, the motivators of an organisation are those things, including its goals, changes to its inputs, etc., which influence its behaviour. In part, this behaviour is the production of outputs, and in part, it is action to sustain the organisation’s continued existence. A significant proportion of a self-maintaining organisation’s inputs can be spent on the latter.

In accordance with the systems principle of requisite hierarchy, every human organisation has a command component. This component is also an organisation. It has a particular role in coordinating the activities of subordinate components, but, in addition, obeys all the general principles of organisations. In the case of an individual person, the command component is the brain. In the case of groups of individuals, it is a high-status individual or sub-group. However, command sub-groups are also organisations with a command component, and recursion occurs until command is ultimately by a single individual. For example, government is the command component of a nation, and in the UK, the Prime Minister is the command component of government. This also helps to simplify what would otherwise be a very complex social structure.

Self-Maintenance

An organisation requires inputs from its environment to carry out its function. Given no changes to the organisation’s internal processes, certain rates of inflow are necessary to sustain certain rates of outflow. For example, the harder a person works, the more food he or she must consume. In the case of a nation, energy, often in the form of oil, is necessary for a certain level of economic output.

All organisations aim to function efficiently, i.e., to maintain themselves and produce their outputs with the least inputs possible. A form of risk/benefit/cost analysis takes place. In individuals and smaller organisations this has an informal and emotional basis, but in larger organisations it can be more formal and have a financial basis.

If inputs alter, or need to be altered, then the command component must decide whether to:

- adapt the organisations internal processes. If so, then, initially at least, increased inputs will be necessary if outputs are not to be reduced.

- influence the organisation’s environment to gain the necessary supply of inputs. This entails use of the organisation’s outputs.

- carry out a combination of the two.

This article will continue with part 2 next week.