Introduction

This article explores two fundamental modes of causal reasoning: TPT (Transfer-Process-Transfer) and PTP (Process-Transfer-Process) structures. These structures help clarify how humans and artificial intelligences like large language models reason about cause and effect, why both are susceptible to error, and why combining them is essential for a robust understanding.

A pdf verion of the article can be downloaded free of charge from: https://rational-understanding.com/my-books#TPTandPTP

The two forms of reasoning derive from the following:

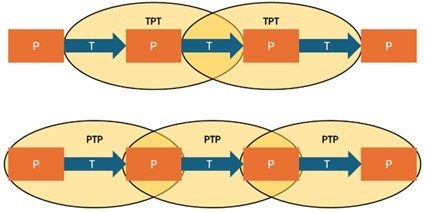

- Causal transfers take time and travelling through any causal network in the direction of the arrow of time will yield a chain of alternating processes and transfers, i.e.: … P – T – P – T – P …

- Causes are effects, and effects are causes.

- Every system or event in a causal chain shares a component with its predecessor and successor.

The PTP structure equates to an event in which something does something to something else. The TPT structure equates to a system with its inputs, processes and outputs.

TPT Reasoning: Pattern Recognition and Unconscious Inference

TPT causality refers to a structure in which two processes are linked by an inferred or unknown transfer, i.e. each cause and effect has the structure TPT and the two are linked by a common T. In human cognition, this reflects pattern recognition: we notice that two processes frequently co-occur, and infer a causal link, even if we cannot identify what mediates the connection.

This form of reasoning is fast, intuitive, and largely unconscious. It allows us to make rapid inferences from experience, often without awareness of the intermediate mechanisms. However, it is error-prone. TPT reasoning is vulnerable to spurious associations and errors caused by unseen common causes. In these cases, the inferred causal link is false, despite the pattern appearing consistent.

Large language models also rely heavily on TPT-type reasoning. They identify recurring associations in their training data and reproduce those patterns in response. This allows them to answer questions, complete prompts, and simulate explanations even when they do not possess internal models of the causal transfers involved.

PTP Reasoning: Explicit Inference and Conscious Verification

In PTP causality, by contrast, causes and effects consist of a process, a known transfer, and another process. Each cause or effect has a PTP structure and the two are linked by a common P. This represents structured reasoning in which a clearly identified mechanism links cause and effect. In human cognition, this kind of reasoning is associated with conscious, reflective thinking. It is slow, deliberate, and effortful, but less prone to error.

Verification through PTP reasoning is essential when pattern-based inferences (TPT) are in doubt. It allows us to examine whether a supposed cause-effect relationship is supported by identifiable transfers. In systems theory terms, it confirms that the output of one process is indeed the input to another.

Error and Verification in Human and AI Cognition

Both humans and artificial intelligences are vulnerable to error when relying solely on TPT reasoning. A classic example is the post hoc fallacy: assuming that because B follows A, A caused B. Without identifying the actual transfer, such reasoning remains speculative.

AI systems, too, may generate plausible but incorrect answers when their training data contains coincidental patterns. They may infer connections that resemble PTP structures but are not grounded in causality.

This is why PTP reasoning is vital for verification. It distinguishes genuine causal chains from coincidental associations by demanding an explicit causal transfer.

A Unified Framework of Reasoning

A key insight from systems theory is that these two modes of reasoning are not exclusive. In fact, they are complementary. TPT reasoning allows for quick hypothesis generation and intuitive understanding. PTP reasoning provides a structure for verification, deeper analysis, and error correction.

Understanding and integrating both types of causal reasoning is central to building a theory of cognition, both biological and artificial. It also has direct implications for epistemology, systems modelling, and the future of AI development.

Conclusion

TPT and PTP causality offer a powerful lens for interpreting human and artificial thought. TPT supports rapid pattern recognition; PTP ensures that those patterns are grounded in real causal mechanisms. Awareness of this dual structure is essential for improving reasoning, communication, and the development of intelligent systems.

Future work may involve identifying when to trust each mode, and how to better integrate them in education, epistemology, and machine reasoning architectures.