This article generalizes the principles of biological evolution so that their broader application can be seen more clearly, particularly in the context of human society and cultural evolution. I will begin with the definition of some general terms, then use these terms to describe general evolutionary principles.

Definitions

A living holon is any organism, any group of organisms, or any group of groups that work together with a common purpose. Human holons are a subset of living holons. They include individual people and organisations of all types from clubs, through businesses and nations, to the global community.

The principles of evolution apply to living things such as bacteria, trees, and people, and some of their artifacts such as factories and computers. They do not apply to other non-living things. This is because living things and their artifacts are derived from a design which can change. Other non-living things, such as planets, rocks, etc. may be derived from a design, but it does not change.

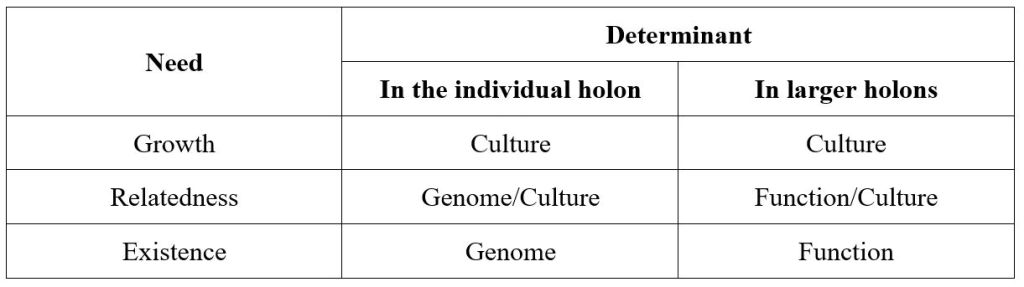

The design of something comprises the information necessary to create the physical manifestation of that thing. Thus, the genome of an organism can be regarded as its design and the phenotype as its physical manifestation.

Culture includes the values, norms, knowledge, and beliefs that govern the behaviour of a living holon. So, the culture of a living holon can be regarded as its design, and the set of behaviours or society of that living holon as its physical manifestation.

The genome of an organism and the culture of a living holon are passed on from generation to generation. Both are also subject to evolutionary change. Randon mutation can occur in the genome due to the influences of viruses, radiation, copying errors, and so on. Random mutations can also occur in culture due to new norms, values, knowledge, ideas, and beliefs.

Satisfiers are those external things that increase the level of satisfaction of the needs of a living holon. Contra-satisfiers, on the other hand, reduce that level of satisfaction. All living holons are motivated to acquire satisfiers and avoid contra-satisfiers. Random mutations in the genome or in the culture of a living holon make it either more or less able to acquire satisfiers or avoid contra-satisfiers.

The status of a satisfier or contra-satisfier can be any one of the following: absent; latent, i.e., promised or threatened; precarious, i.e., present but not necessarily so in the future; or entrenched, i.e., present and likely to remain so. This discussion concerns satisfiers and contra-satisfiers that are precarious or entrenched.

The principles of evolution apply to populations of living holons in the following ways.

Evolution under the effect of contra-satisfiers.

When a contra-satisfier that impacts on a living holon’s ability to survive and procreate is applied to a population of living holons, then those most able to avoid it are more likely to survive and procreate than those least able. This ability to avoid the contra-satisfier stems from the design of the holon, i.e., its genome or culture. Thus, genetic or cultural attributes that enable avoidance of the contra-satisfier are selected for, and the proportion of those better able to avoid it steadily increases. Advantageous genes or ideas will propagate through the population and disadvantageous ones will expire.

Evolution under the effect of shortages of satisfiers.

When a shortage of a satisfier that impacts on a living holon’s ability to survive and procreate is applied to a population, then those best able to acquire the satisfier are more likely to survive and procreate than those least able. Again, through natural selection, the proportion of those better able to acquire the satisfier steadily increases.

The evolution of cooperation.

Although this is not always the case, one way of becoming better able to acquire a satisfier is to form a co-operative group, and thus, a shortage of satisfiers can also lead to the evolution of cooperation. By acting together, it may be possible for more than one holon to acquire a mutual satisfier or avoid a mutual contra-satisfier from the environment. When the members of a holon act together in this way, they exchange satisfiers with the holon’s control component or leader. This often takes the form of information flowing upwards and instructions flowing downwards. It is also possible, but not necessarily so, for them to exchange satisfiers with one another. In this way, a cooperative group, and thus, a higher-level holon is formed which follows the same general laws as the original holons. Thus, the higher-level holon can act cooperatively with others to form yet higher-level ones. If holons benefit more, in terms of their survival and procreation, by acting together rather than independently, then the former are more likely to survive and procreate than the latter. So, the genetic or cultural attributes which lead to cooperation will steadily propagate through the population over time.

However, cooperation will of course fail if it does not lead to the desired result.

We tend to focus on our failures, and this obscures the fact that human beings are extraordinarily cooperative. Were this not the case then our societies which comprise millions of people, and sometimes even billions, would collapse.

This is the basis of multi-level selection theory, i.e., the survival and procreation of an organism depends on the survival of cooperative groups or holons to which it belongs. Furthermore, multi-level selection theory applies not only to individual organisms but also to higher level holons. The survival of any higher level holon also depends on the survival of yet higher level ones to which it belongs. Such holons are formed by their culture, and so, multi-level selection theory also applies to cultural evolution.

The existence of leaders with dark personality traits can also be explained by this process. The lower the level of a holon the more it contributes to the survival of the organisms that comprise it. Leaders with dark traits may be perceived as beneficial to the survival of that holon, and thus, the organisms that comprise it, even this is at the expense of potentially higher level holons. However, evolution cannot predict the future and the highest level holon, humanity, is now at risk from dark leaders. So, such leadership must not be allowed to continue if we are to survive.

Competitive co-evolution.

It is possible for two populations of living holons to compete to acquire the same satisfier or avoid the same contra-satisfier. In this case, both populations evolve to become ever more capable. Ultimately, one may succeed and the other may expire. But until that time, neither fully succeeds because of the evolution of the other, and ongoing evolution causes the two to become ever more specialised.

As in the case of predation, where two populations A and B are involved, it is also possible for A to provide B with a contra-satisfier and for B to provide A with a satisfier. In other words, what may be a satisfier for one may be a contra-satisfier for the other. Evolution will result in population A becoming better able to acquire the satisfier and population B becoming better able to avoid the contra-satisfier.

Finally, as in the case of conflict, it is possible for the two populations of living holons to deliver contra-satisfiers to one another. Evolution will result in both being better able to deliver them, but also in being better able to avoid them. Ultimately, however, one party is likely to prevail and the other to expire.

Cooperative co-evolution.

Cooperation comprises the exchange of satisfiers between two parties. If the two parties have different functions, and the receipt of a satisfier from the other party affects their ability to survive and procreate, then cooperative co-evolution will occur. Genetic or cultural traits that better enable one party to acquire the satisfier from the other will propagate through the population. Genetic or cultural traits that enable one party to deliver the satisfier to the other more efficiently, i.e., using fewer resources, will also propagate through the population. Over time, this can result in both parties becoming highly specialised and dependent on one another.