Introduction

Every system, from molecules to minds to markets, changes over time. These changes are not random. Systems tend to follow patterns: settling into stability, reacting to shocks, and sometimes undergoing deep transformations. One of the most powerful ways to understand this behaviour is through the medium of energy landscapes, a concept that is well established and widely used in physics.

Systems undergo phase transitions, a term borrowed from physics. When water freezes to ice, it experiences a type 1 phase transition; the change occurs almost instantaneously across the entire system. More complex systems, however, typically undergo a type 2 phase transition; one that requires them to traverse an energy landscape, moving step by step between stable states. Over geological time, for example, the Earth has shifted through such a landscape from a predominantly mineral state to a living one and may now be transitioning toward an informational one.

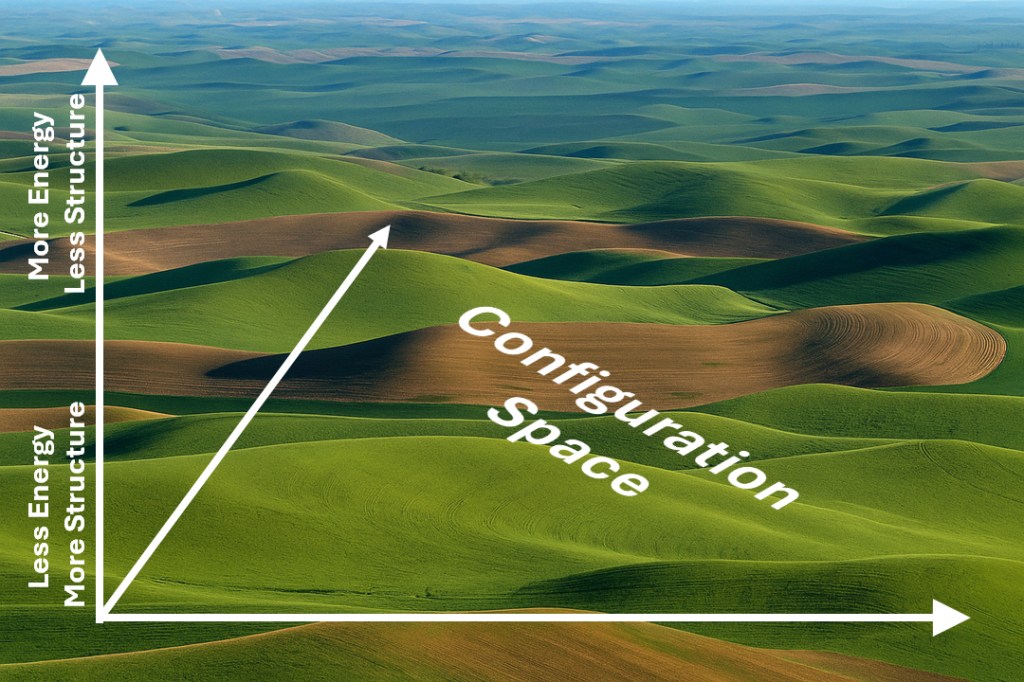

An energy landscape is a conceptual tool that maps all the possible configurations a system can take and shows how stable each of those configurations is. It is not a feature of the system itself, which at any given time exists in just one of those configurations. Instead, it is a representation of the system’s entire configuration space, i.e., the set of all possible arrangements of its components, whether or not those arrangements actually exist. While it is helpful to imagine this landscape in two dimensions, in practice it may have hundreds, thousands, or even millions of dimensions.

A system can be closed; that is, no energy or matter enters or leaves it; open to energy; or open to both energy and matter. The nature of the landscape differs for each. This is explained in more detail in the paper “Framework for a General System Theory” (Challoner, 2025) available at https://rational-understanding.com/2025/05/12/framework-for-a-general-system-theory/.

In the open systems encountered in nature, valleys in the energy landscape represent stable, low-energy states (also called attractors) where systems tend to settle. Hills or peaks are unstable, high-energy states where systems rarely remain for long. Over time, systems “move” across this landscape in response to internal dynamics and external influences.

In this context, internal dynamics refers to changes that arise from within the system itself, without major external shocks. In physical systems, this might be thermal fluctuations or ongoing chemical reactions; in biological systems, metabolic processes or genetic variation; in social systems, demographic shifts, gradual changes in norms and institutions, or structured cycles of change such as Margaret Archer’s Morphogenetic Cycle. Over time, these small, cumulative adjustments can alter the system’s configuration, nudging it toward a new position in its energy landscape.

If left undisturbed, however, most systems drift toward the lowest nearby valley; the most stable state available.

The Structure of Systems and Their Landscapes

To understand what defines a system’s configuration space, we need to know what the system’s components are. Systems theory describes reality as a nested hierarchy; each system is made of subsystems, which are themselves made of smaller subsystems, and so on. Assembly theory offers a compatible view from another angle; it sees every system as built from previously assembled components that themselves have been assembled from simpler, previously assembled parts.

Assembly theory assigns levels of assembly. The simplest structures occupy level 1. Assemblies made from level 1 components occupy level 2, and so on, increasing in complexity. Thus, any system can be described as level n, and composed of level n–1 components. The latter are, in turn, made of level n–2 sub-components, and so on.

The configuration space of a system of level n is defined by the degrees of freedom of its level n–1 components, that is, the independent ways in which they can vary.

Open System Energy Landscapes

An open system energy landscape maps the total energy of a system onto the configuration space of its components. In the simplified three-dimensional visualisation, valleys (low total energy) correspond to stable attractors. They are typically associated with high organisation and high “information at source”. Peaks, on the other hand, are unstable configurations, typically associated with high total energy, low organisation, and low “information at source”.

Figure 1 – An energy landscape visualised as hills and valleys in a two dimensional terrain.

In this framework, “information at source” is equivalent to Schrödinger’s negentropy, i.e., the degree to which a system’s entropy is less than its maximum possible value. Thus, in an open system energy landscape, valleys correspond to high-negentropy states, while peaks correspond to high-entropy states.

Static and Dynamic Landscapes

In open systems that are closed to mass but open to energy the landscape is relatively static. As energy enters or leaves a system its energy landscape moves up or down whilst retaining the same overall profile. An example that approximates to such a system is the Earth as a whole, which receives energy from the Sun but gains little matter.

However, not all energy landscapes are equally stable. Systems open to both energy and mass have landscapes that are dynamic, shifting like the surface of a storm-driven ocean. In such systems, attractors can deepen, vanish, or be replaced as new matter and energy flow in or out.

Natural systems such as coastal estuaries, and social systems such as globalised manufacturing, both illustrate how being open to energy and mass makes a landscape dynamic. In an estuary, tides, storms, and seasonal floods bring new sediment, nutrients, and species, reshaping which ecological communities dominate. In manufacturing, new technologies, raw materials, and workforce movements can build new industrial hubs or undermine existing ones. In both cases, stable configurations, ecological communities or production networks are attractors, but these can deepen, vanish, or be replaced entirely as continual flows of matter and energy reshape the landscape.

How Systems Traverse a Landscape

Over their lifecycles, open systems tend to shift into progressively deeper valleys, i.e., more complex and stable forms of organisation, until they are constrained by internal limits such as resource shortages or diverted by external shocks. Initially, a collection of components is only a subcritical structure; it lacks the emergent properties necessary for the novel functions and outputs lacked by its parts. As organisation increases, it may become a sub-optimal system, i.e., one that has an emergent function, but not yet enough structure to deliver outputs efficiently. Further organisation can lead to an optimal state, where the energy used for structural maintenance and the energy used for output are balanced to maximise performance. Beyond this point, the system becomes super-optimal; any additional complexity may draw too much energy into self-maintenance, reducing output and eventually leading to collapse if maintenance demands outstrip available energy.

Systems can also oscillate around an attractor, making continual small adjustments to remain stable. In real-world settings, such oscillations often produce repeating cycles, e.g., periods of growth followed by contraction, tension followed by resolution, or stability punctuated by brief disruptions. Over time, these cycles can reinforce the system’s current organisation, allowing it to return to the same attractor after each disturbance, a tendency known in systems theory as equifinality. However, if the oscillations amplify or are combined with large external shocks, the system may break from its cycle and transition into a different valley entirely, reorganising around a new attractor, a process referred to as multifinality. In social and ecological systems, such transitions may take the form of reorganisations, revolutions, or collapses.

Fractality in Energy Landscapes

Energy landscapes are often fractal. That is, similar patterns appear at different locations and scales. This arises because many configurations are variations of others. For example, components may be identical, allowing them to be interchanged without altering the whole, so different areas of the landscape share the same pattern. In addition, systems frequently assemble recursively, meaning that smaller subsystems are built in the same way as the larger system they belong to. This repetition of assembly patterns across levels produces repeating structures in the landscape itself: the routes to forming a subsystem resemble the routes to forming the whole, creating self-similar pathways and clusters of attractors at multiple scales.

This fractal nature means that, as a system traverses its energy landscape, patterns of change it has followed before may reappear later in its life, and often at different scales. Because similar configurations and pathways exist in multiple locations across the landscape, the system can encounter familiar transitions in new contexts. This is why history can sometimes guide our expectations, although the self-similarity of the landscape never guarantees identical outcomes. For example, in ecology, the process by which vegetation colonises bare ground after a small landslide can resemble the much larger-scale succession that occurs after a volcanic eruption. The sequence of pioneer species, intermediate communities, and mature forest repeats the same general pattern, even though the scale, timing, and specific species differ. Similarly, in economics, a localised boom-and-bust cycle in a single industry can follow the same trajectory as a national economic cycle, but on a smaller scale and over a shorter period.

This fractal nature also means that systems can become trapped in “valleys within hilltops”. That is, zones of local stability nested inside larger instabilities. In such cases, a system may appear stable in the short term while, in reality, the broader configuration it occupies is unstable and heading toward change or collapse. For example, a government may maintain political stability through a fragile coalition, yet the entire national system faces deepening economic and environmental crises that will eventually destabilise it. Similarly, a supercooled liquid can remain in a seemingly stable state until the slightest disturbance triggers a complete and irreversible phase change.

From Physics to Society

The concept of energy landscapes is not limited to physics or chemistry. Social systems, such as international relations, also move across landscapes defined by stability and change. These systems are open to new energy in the form of ideas, movements, and crises, but largely closed to new matter, since nations rarely appear or disappear. Like physical systems, they experience periods of self-maintenance, oscillation, disruption, and transformation. And just as in natural systems, their landscapes can be reshaped by sustained flows of energy or sudden shocks.

Conclusion

Energy landscapes offer a way to see not just where a system is, but how it might change. They explain why systems settle into certain patterns, why some shocks cause sudden transitions while others do not, and why some paths are easier to follow than others. They also show how patterns can repeat, recombine, and evolve over time. By viewing systems through this lens, and by recognising that landscapes themselves can shift, we gain a powerful method for thinking about change in everything from molecules to markets.

2 replies on “Understanding Energy Landscapes”

Hello John

I think this is a very interesting view but highly descriptive, symbolic framework is needed which would make all this more concrete

Best take care in this horrible heat jns

LikeLike

I agree Janos. Statistical physicists do have mathematical techniques for tackling energy landscapes. So that would be the starting point for anyone wishing to follow up on your suggestion.

LikeLike