In sociology, the term “functional differentiation” describes progressive specialisation within a society. This concept has long been well understood, but was brought to prominence by the American sociologist, Talcott Parsons, and the German one, Niklas Luhmann. Functional differentiation is a major contributor to increasing social complexity, and a feature of Western society today. When a society is relatively stable, ever-increasing knowledge and population leads to ever more specialisation, and organisations to carry out specialised activities. Up to a point, functional differentiation generally leads to increased efficiency, and is therefore beneficial to society. Unfortunately, however, it also leads to increasing communication distances, and thus, an increased risk of miscommunication. It also leads to ever more complex functional dependencies, i.e., reliance on a greater number of other organisations for the inputs needed to carry out one’s own function. This leads to an increasing risk of organisational failure. Functional differentiation can also lead to a reduced understanding of the roles of others, and thus, to potential conflict, and potential failure of the parent organisation. Finally, as will be discussed a future article, it can lead to an increasing risk of mental ill-health.

So, unless these disbenefits can be reduced, by for example improving information technology, there may be an optimum level of functional differentiation beyond which the benefits begin to decline.

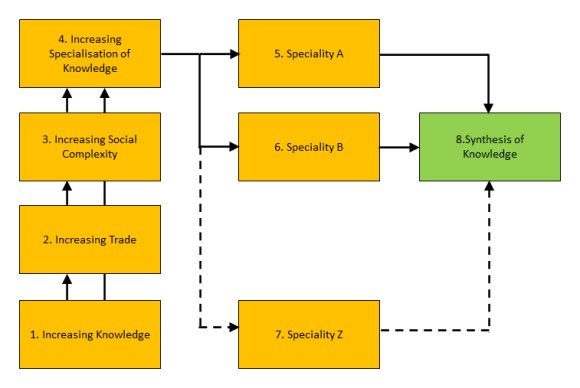

The academic sector provides an example of functional differentiation. This is summarised in the diagram below.

Our increasing knowledge has led to an increasing number of goods and services, and thus, to greater trade. This, in turn, has led to increasing social complexity which, alongside greater knowledge, has led to the formation of academic silos. Specialists now share knowledge mainly only with other specialists in the same discipline. There is a relative lack of cross-disciplinary sharing. This has developed to the point where the knowledge in one field can be incomprehensible to those working in another. As a consequence, our ability to identify inconsistencies between different branches of knowledge has reduced. Furthermore, our ability to draw on knowledge from one field to enhance that of another has also declined.

Specialisation will always be necessary. However, there is also now a pressing need for generalists, i.e., people with the knowledge and understanding of more than one speciality to carry our this cross-disciplinary work. Whilst the latter is now widely understood, the academic world has become highly institutionalised and is difficult to change. Limited moves are being made to introduce cross-disciplinary courses, but these are often little more than a year spent in another department. The following article in The Guardian provides further information: https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2018/jan/24/the-university-of-the-future-will-be-interdisciplinary

To date, however, relatively little work is being done to develop cross-disciplinary comparison techniques or to train students in their use, and this needs to change. Ironically, cross-disciplinary comparison is itself is a speciality and includes, for example, logic, epistemology or the theory of knowledge, causality, systems science, and poly-perspectivism.

So, there are ways to tackle the downsides of functional differentiation in the academic world. Similar techniques can be applied elsewhere.