In this article, I use social systems theory to explain how cooperative arrangements can fail. I will use the topical example of labour relations in business to illustrate this, although there are many other examples such as cooperative relationships in families, between friends, and between nations. The example that I have chosen reveals little that we do not already know from experience. However, this is not the purpose of the article. Rather, its purpose is to demonstrate how the underlying principles of social systems theory result in a model that reflects reality.

The example began as a series of equations, each of which, drew on the principles of ecology to describe a relationship between two unspecified parties. The principles of evolution were then used to link the equations and demonstrate how these relationships could change over time. Finally, the series of equations was translated into the text below.

The example is limited to a discussion of relationships within the private business sector. This sector interacts with many others such as education, healthcare, government, the legal sector, and so on. For the purposes of this article, only a brief discussion of interactions with government is included. Interactions with other sectors have not.

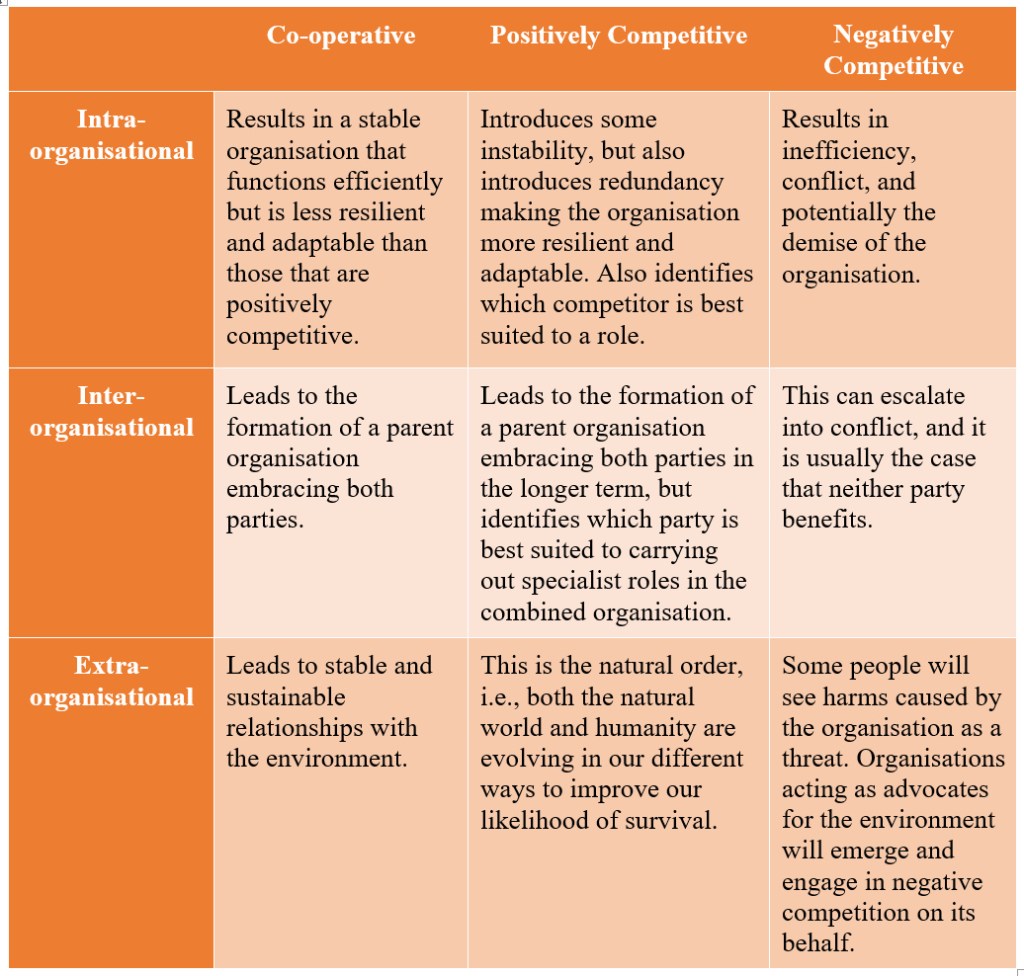

Cooperation, or as it is known in ecology, mutualism, occurs when two parties work together with a common purpose. The parties involved can be individuals or organisations of any type or size, including families, businesses, voluntary organisations, governments, and nations. Their purpose is usually to gain satisfiers or avoid contra-satisfiers for their mutual benefit. The source of these satisfiers or contra-satisfiers is a third party or the general environment. Satisfiers are those external things that satisfy the needs of an individual organism, group of organisms or species. Contra-satisfiers on the other hand are external things that reduce the level of satisfaction of those needs. For example, the employees and employers in a business cooperate to manufacture and sell goods to their market for a profit. This profit is a satisfier for the needs of both parties and is shared between them for their mutual benefit.

Initially, two parties in a cooperative arrangement may be relatively equal in power. However, as time progresses, one invariably gains greater power, and so, the benefits of the arrangement are shared less equitably. In a business, for example, employers typically come to hold greater power. However, there have been cases in which, through trade union organisation, employees have come to do so instead.

Two things can then occur. Those with greatest power can seek ever greater power, and thus, ever more inequitable distribution of the benefits of cooperation. Alternatively, or additionally, a shortage of the mutual satisfier can occur. For example, the market for the business’s product may decline.

There is a threshold above which parties will voluntarily cooperate, and below which they will not. For example, if employees are to co-operate with employers, then the wages gained from employment must be sufficient to satisfy their needs. Employers, on the other hand, must be able to satisfy their own personal needs and those of the business. If one party takes too much of the benefits and/or if the market for their product fails, then the other party may find the benefits of co-operation insufficient. The owners may no longer be able or willing to pay enough to make employment worthwhile, or the returns for the employers may no longer be sufficient to make the business worthwhile. So, one party may find itself cooperating involuntarily with the other. For example, the employer may, in effect, be taking the employees’ labour against their will, although the reverse is also possible.

When one party takes a satisfier from another and the other party a) needs it to satisfy their needs and b) has no resilience or rainy-day surplus such as savings or capital, then the former party is, in effect, imposing a contra-satisfier on the latter. As a consequence, there is a risk of conflict, and three courses of action are possible.

To avoid conflict, the weaker party can move elsewhere. For example, employees can resign and look for alternative employment, or employers can close the business. Cooperation then ceases. In ecology, this is known as neutralism.

Alternatively, because the imposition of a contra-satisfier by one party on another normally results in reciprocation, the two parties can engage in conflict. The purpose of reciprocation is, of course, to coerce the employer or employees into a more equitable apportionment of the business’s benefits.

Finally, the one party can accept harmful exploitation by the other. It is an objective fact that, in ecology, harmful exploitation is known as predation or parasitism. These terms are not intended to be disparaging.

Much depends on the relative power of the two parties. If the harmful exploitation of employees is widespread, there may be nowhere for employees to move to. If general employee power is too great, there may be no alternative business opportunity for the employers. In these circumstances, the only options that remain are conflict or the acceptance of exploitation. If either party has so much power that conflict with them will inevitably fail, then only the final option, an acceptance of exploitation, remains.

Co-operation can, of course, fail even when the parties are relatively equal in power and the benefits of a business are shared reasonably equitably. If these benefits should fail for any reason, e.g., market collapse, competition, etc., then, providing they have reserves of the necessary satisfiers, both employers and employees may find themselves in the position of being harmlessly exploited for a while. A reasonable degree of resilience by both parties is, therefore, needed to retain co-operative arrangements during short term market downturns, etc. However, if these reserves become exhausted, then harmless exploitation becomes harmful, i.e., a contra-satisfier, and so, co-operation fails.

The following conclusions can be drawn from this example. If employers gain too much power and are unwilling to share the benefits of businesses sufficiently equitably to satisfy the needs of their employees, then they will fail to gain the latter’s voluntary cooperation. Conflict can then become widespread and lead to economic failure with disbenefits for all. Alternatively, harmful exploitation can become widespread, and we can come to live in an authoritarian society. Employers can, of course, tread a careful line and share benefits just sufficiently equitably to make employee cooperation worthwhile. However, because there will be no employee resilience, when a shock to the business occurs, this can quickly cause cooperation to be lost.

Conversely, if employees gain too much power and demand excessive pay, then this can prevent growth, reduce business resilience, and thus place, the business’s continued existence in jeopardy. Again, co-operation will break down, and the benefits to both parties will be lost. If this situation becomes widespread, then only those employees who are organised will benefit, and then only in the short term. Ultimately, economies will fail to grow, and the benefits of this growth will be lost. In the extreme, economies can collapse, and poverty can become endemic.

The way forward, therefore, is a middle road in which the balance of power between employers and employees is optimised. This is the role of national government which, in an ideal world, should exercise it scientifically, objectively, non-ideologically and without undue influence from either employers or employees. It is worth mentioning that corrective legislation to curtail excessive power of either employers or employees should not be retained indefinitely. Rather, it should be rolled back once an optimum balance is achieved. Failing that, the optimum will be overshot, and the power of the other party will steadily increase. If they are to retain an optimum balance, governments should keep their eye on the ball and amend legislation as necessary.