Culture

Culture is learned and comprises values, norms, beliefs, knowledge, and symbols. It is, therefore, information. A culture can be shared by the members of any organisation small or large. Culture, especially values, along with inherited predispositions affect a person’s behaviour, and thus, the “style” of interactions between and within organisations. The style of interaction also affects the culture of an organisation and there is, therefore, a degree of feedback between the two.

The social environment in which an organisation operates has a strong bearing on its culture. However, not all organisations operate within a single environment. Some, for example, operate globally. Furthermore, not all individuals or organisations concur with the culture that prevails in their environment. Leaders of an organisation also have a strong influence over its culture. These factors can result in conflicting values, the consequences of which will be discussed in a future article.

Interaction style

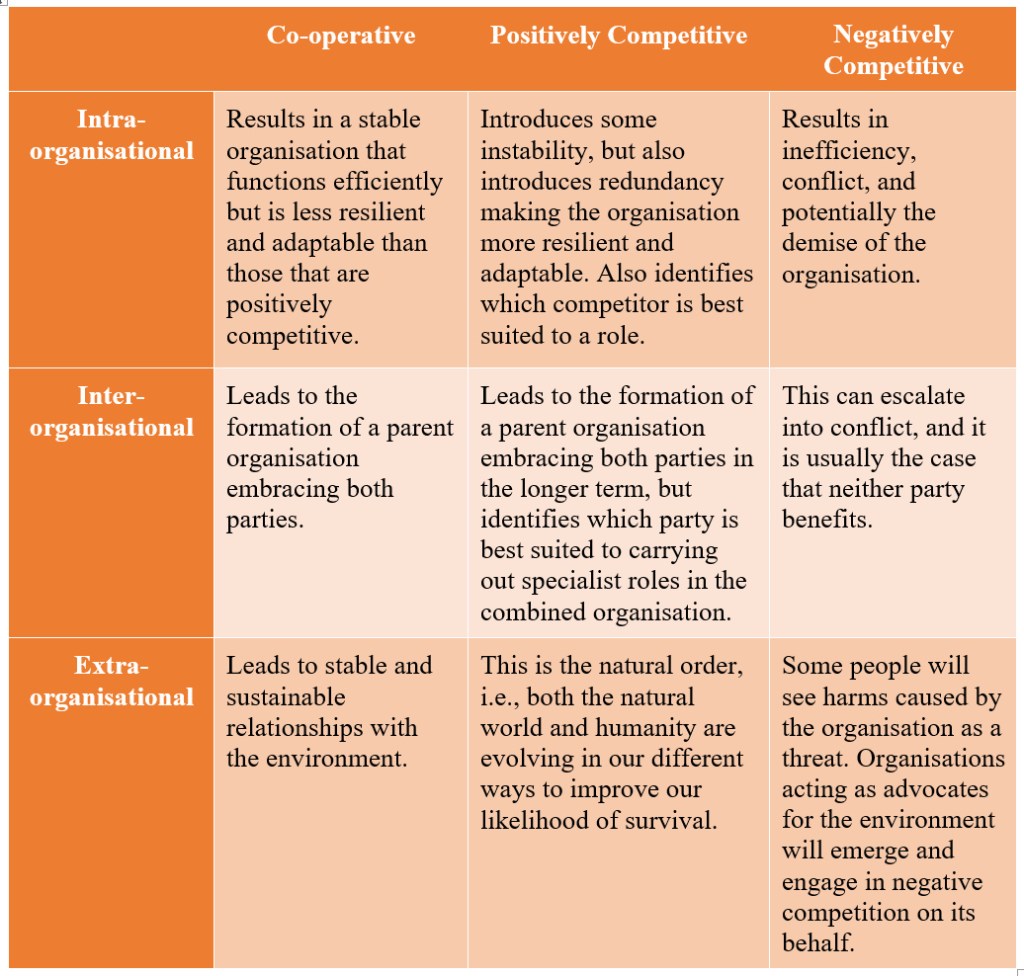

Organisations are predisposed to interact in one of three basic styles: co-operation, for example, helping one another over the finish line in a race; positive competition, for example, running as fast as we can to be first over the line; and negative competition, for example, kicking the legs out from one another on our way to it. This predisposition is based on past experience and learning from others in the community but actual interaction style also depends on circumstances.. In the case of co-operation and negative competition, the two organisations interact directly with one another. Co-operation involves an equitable exchange of satisfiers; negative competition involves an exchange of contra-satisfiers. However, in the case of positive competition, the two organisations do not interact directly, but rather with a third party. This is usually a precursor to co-operation between the third party and the successful competitor.

In practice, the predispositions of organisations are often a mix of the three interaction styles, each predominating in different circumstances, as shown in the diagram below.

The style of interaction is usually, but not necessarily, defined by the attitudes of the component organisations or individuals directly involved in the interaction and te circumstances. However, more senior leaders can have an influence through their leadership style, the culture they promote within the organisation, and their distance from the interaction.

Interactions can be vertical, i.e., between individuals or organisations above and below one another in a hierarchy. They can also be horizontal, i.e., between individuals or organisations at similar levels, but on different branches, of a hierarchy. Thus, for example, the interaction between a manager and a junior member of staff is vertical, and the trade between nations horizontal.

Vertical Interaction Style

Vertical interaction is a special case of interaction in general. True leadership and followership are co-operative, but this form of interaction does not always exist between senior and junior individuals or the components of organisations. A leader must be accepted by followers to gain their willing support. If the leader is appointed by a bottom-up process, i.e., if followers agree their leader, then co-operation will normally ensue. However, if a leader is appointed by a top-down process, then co-operation is not inevitable, and positive or negative competition may occur. Examples of top-down appointments include not only appointments made by senior managers, but also business takeovers and the invasion of nations.

In positive competition, the two parties do not interact with one another but compete for satisfiers from a third party. An appointed leader and an unwilling follower may, for example, both compete for recognition by a more senior person.

In negative competition, contra-satisfiers are exchanged but the leader or parent organisation is normally in a more powerful position, and thus, able to coerce the follower with threats of contra-satisfiers. Fortunately, extreme examples of such behaviour are now largely illegal, but mild versions persist in many organisations.

The style of vertical co-operative interaction varies on a scale. At one end is the personal contract, i.e., trading of personal benefits, such as power, wealth, and influence for support. At the other end of the scale is Rousseau’s social contract, which states that followers are willing to give up some of their rights in the communal interest. However, the definition of communal interest can vary, and so the social contract can be defined in several ways. Thus, this definition should be revised as follows: people are willing to support a leader, and thus, give up certain rights if that leader acts in a way that delivers benefits to:

- the individual supporter (personal contract);

- the supporting team (team contract);

- the sub-organisation (sub-organisational contract);

- the organisation (organisational contract);

- the super-organisation (super-organisational contract);

- the nation (national contract);

- humanity (species contract); or

- the ecosystem (environmental contract).

The style of contract sought and offered will depend on the follower’s and leader’s attitudes. In general, the weight given to each type of contract, i.e., its relative influence on their interaction style, generally decreases from personal, to social, to species, to environmental. This decrease is consistent with the multilevel selection theory of evolution. We place greatest weight on immediate personal interest, but do not neglect our longer-term interests gained communally. The actual weights applied by an individual or organisation depend on their attitude. Generally, those with a right-wing attitude will place greater weight on the personal contract, and less weight on other contracts, than those with a left-wing attitude.