Introduction

In this article I summarize previous ones on human interaction, explain that this is based on our perception of others, and introduce the topics of prejudice and discrimination. The latter topics are very emotive, particularly for those who have experienced them. However, I have endeavored to describe the social and psychological processes behind them objectively.

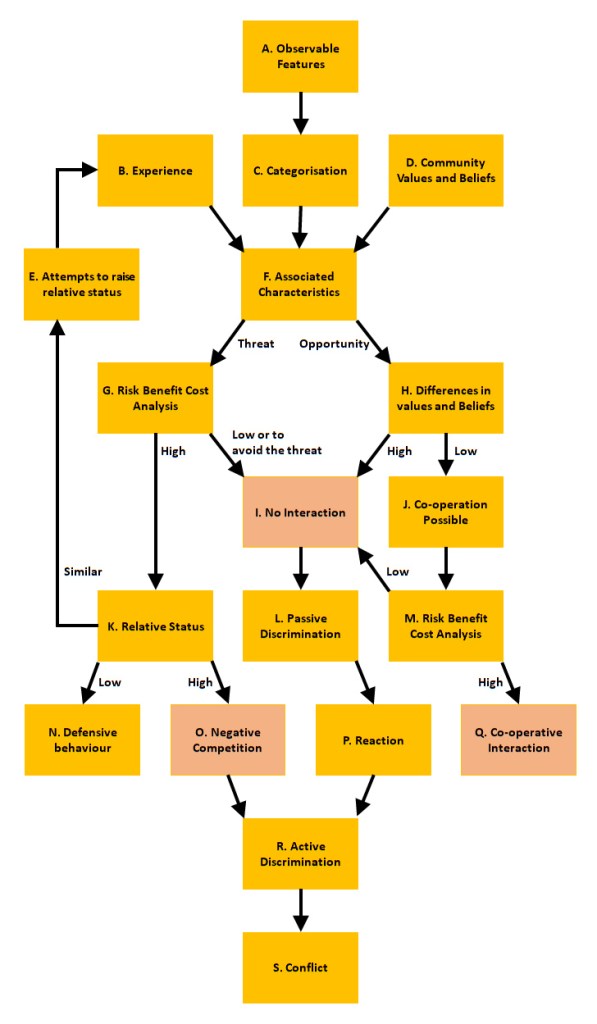

These processes are complex, and the discussion relatively long. So, to assist the reader, I have provided a diagram. Letters in the text, e.g., (A), refer to relevant parts of the diagram.

Although the discussion focusses on interactions between individuals, the same principles also apply to organisations of all types, including nations.

The nature of interaction

Interaction is a form of trade, and thus, reciprocal. We cannot interact with someone who ignores us. However, it is not merely the trade of material goods and services for money, but rather a more general trade of satisfiers and/or contra-satisfiers. That is, anything that satisfies our needs, e.g., food and shelter, or helps us to avoid contra-needs or harms such as social exclusion or illness. This can include intangible satisfiers such as friendship, inclusion, information, advice, emotional support, and so on. It can also include intangible contra-satisfiers such as threats, exclusion, violence, etc.

Priorities & the thresholds for interaction

There are three forms of interaction: co-operation, negative competition, i.e., attempting to harm the other party or prevent them from attaining their goals, and no interaction.

The Goldilocks Zone hypothesis for interaction has a part to play in our decision whether to interact with another party or not (H). It acts as a first filter. As a rule, although there are exceptions, we tend to favour co-operative interaction and to avoid negative competition. If the values and beliefs of someone with whom we might interact are thought to be the same as or like our own, then co-operation may be possible (J). If their values and beliefs are thought to differ greatly from ours, then it may not. However, rather than engaging in negative competition, we will usually try to avoid interaction (I).

All interaction consumes resources, particularly time. However, our resources are limited and so too, therefore, is the number of people with whom we can interact. The British anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, estimates that the number of stable relationships an individual can maintain is approximately 150. So, like any other activity, we prioritise our interactions using a subjective form of risk, benefit, cost analysis (M). This acts as a second filter.

Those with whom we choose to interact co-operatively, are those we perceive as being likely to provide the greatest benefit for the least effort. In this context, benefit is the satisfaction of our needs or the avoidance of our contra-needs. Because our resources are limited, there is a cutoff point in the risk, benefit, cost analysis below which we will not interact (I). For example, if someone offers low payment for a day’s work then we may not consider it worth the effort.

If we do wish to interact, then the benefits that the other party anticipates by reciprocating must also exceed their risk, benefit, cost threshold. If it does, then interaction and the trading of benefits can proceed (Q). Reciprocation does not always occur, of course, and this can lead to some frustration.

In some cases, the other party will be thought to pose a threat. Again, a form of risk cost benefit analysis is carried out (G). If the threat falls below our threshold, we will not interact (I).

In summary, therefore, we will not interact with others:

- whose perceived values and beliefs are so different from ours that we believe co-operative interaction to be difficult or impossible, or

- who are thought to offer insufficient benefit, or

- who fail to reciprocate, or

- who are thought to pose an insufficient threat.

The categorization of people and the nature of prejudice

All human beings lack the mental capacity to know everything in detail, including the vast majority of people in the world. So, we place everything, including people, organisations, and nations, into types or categories (C). In the case of people and groups of people, this is based on their physical appearance, and the culture, values, beliefs, and behaviours that they outwardly display (A).

We then associate certain characteristics and behaviours, including threats and opportunities, with these categories (F). We learn these associations not only from experience (B) but also from information provided by our community (D). Unfortunately, the latter can include errors, misinformation and propaganda.

Everyone, without exception, must categorise others in this way, and associate behaviours with those categories. This simplification is necessary because of our limited mental capacity. It is an evolved trait that enables us to make a first order approximation of the likely behaviour of someone or something. This includes any threats or opportunities that they may pose.

It is important to note, however, that it is not the external symbols used to create categories that are the cause of our reactions to their members, but rather the characteristics and behaviours that we associate with those categories. Unfortunately, those associations can be false, particularly when they have been acquired from others.

When our categorization of people would, if it influenced our behaviour, result in harm to them, then we refer to this as prejudice. This is particularly, but not exclusively, the case when we categorise less powerful minorities.

Power, hierarchies, & how relative position in a hierarchy affects interaction

Those who hold a particular set of values or beliefs form a group, and the power held by that group is the aggregate of the power held by its members. This power is based on the control of resources, for example wealth, influence, and the control of satisfiers such as jobs. It is also based on the ability to provide satisfiers such as food, housing, or education, and to inflict contra-satisfiers such as the denial of those things, threatening behaviour or acts of violence.

Hierarchies exist based on the magnitude of the benefits or disbenefits that individuals can offer to or inflict on one another. Furthermore, different hierarchies exist for different benefits. For example, there is a hierarchy of wealth, with an elite at its peak. There is one of knowledge, also with an elite at its peak. Finally, there is one of violence with the most violent, least restrained, and most well-armed people at its peak. Generally, because of the potential benefits, people will endeavour to interact, and so, trade benefits with those at a similar or higher level in a hierarchy, or at similar or higher levels in parallel ones. They will normally only interact with those below them to maintain the hierarchy.

Deciding how to interact, active discrimination and passive discrimination

The category into which we place people determines whether and how we interact with them. If someone is placed in a category associated with an opportunity to benefit, then, providing the risk, benefit, cost assessment exceeds our threshold (M), we will be predisposed to interact co-operatively with them (Q).

If, on the other hand, they are associated with a threat, then, depending on the circumstances, we will either not interact with them (I), or will engage in negative competition (O). We will not interact with someone perceived as posing a threat if this avoids the threat. Nor will we interact if the perceived threat is less than our threshold (I). If failure to interact results in harm to the other party, such as the denial of rights and opportunities afforded to others, then we refer to this as passive discrimination (L).

However, if the perceived threat exceeds our threshold, or if we are obliged to interact for any other reason, then the relative position of that person in the hierarchy, and thus, their relative power, becomes important (K). If they are lower in the hierarchy, then we will usually act aggressively, i.e., engage in negative competition (O). Harms such as social exclusion, financial harm, or violence, will almost certainly result, and we refer to this as active discrimination or persecution (R). On the other hand, if they are higher, then we will usually act defensively, i.e., behave in a manner that avoids the threat (N).

Finally, if two people or groups regard one another as a threat and have similar status in a hierarchy, then negative competition will be reciprocal. Both parties will attempt to gain higher status in order to prevail, and this can increase the perception of a threat (E). So, positive feedback can occur and can ultimately lead to violent conflict (S).

Passive discrimination can lead to active discrimination and social unrest in the following way. If people lower in a hierarchy experience passive discrimination (L) and are denied the opportunities of others, then they will feel resentment towards the perpetrators and experience anomie. That is, a breakdown of those values and beliefs that they previously shared with society. Thus, they may engage in criminality or other anti-social activities (P). This, in turn, can create apparent justification for the original categorization of those people and lead to active discrimination (R). So, the original prophecy becomes self-fulfilling. When active discrimination occurs, the victims may seek to retaliate via some other hierarchy in which they hold greater power (R). This can often take the form of aggression or violence (S).

Summary

- Interaction is the reciprocal trade of satisfiers and/or contra-satisfiers.

- There are three forms of interaction: co-operation (Q), negative competition (O), and no interaction (I).

- As a first filter, we believe that we can interact with people whose values and beliefs (H) are thought to be like our own (J), but not with those whose values and beliefs differ significantly (I).

- As a second filter, we prioritise possible interactions using risk, benefit, cost analysis (G & M), where “benefit” means the satisfaction of our needs and the avoidance of our contra-needs or harms.

- Finite resources limit our ability to interact. So, if a perceived benefit or threat is below our risk, benefit, cost threshold, then we will not interact (I).

- We interact with other people based on perceived opportunities to benefit and perceived threats (F).

- Our perception of these opportunities and threats is based on the categorization of people (C) and the association of benefits or threats with that category (F). This association is gained from experience (B) or learnt from others (D). However, the latter can comprise misinformation or propaganda.

- Prejudice is when categorisation, if it were to influence our behaviour, would lead to the other party being harmed.

- Power is the aggregate of the power held by members of a group with a shared set of values. It is based on their control of the resources that can provide satisfiers or contra-satisfiers to others.

- Hierarchies exist based on the magnitude of the satisfiers and contra-satisfiers that people can offer to one another (K).

- We tend to interact with those higher in a hierarchy and only interact with others if this maintains a hierarchy to which we belong.

- We will attempt to avoid interaction with others perceived as posing a threat if this avoids the threat (G & I).

- Passive discrimination is an absence of interaction that leads to the other party being harmed (L).

- If obliged to interact with someone thought to pose a threat and higher than us in a hierarchy, then we will behave defensively to avoid the threat (N). If they are below us in the hierarchy, then we will engage in negative competition, i.e., behave aggressively (O).

- If we interact with someone of similar status in a hierarchy and thought to pose a threat, then both parties will engage in negative competition and attempt to raise their status (E). This causes a feedback loop which raises the apparent threat for both and can ultimately lead to conflict (S).

- Active discrimination is negative competition that leads to the other party being harmed (R).

- Passive discrimination leads to criminality and resentment (L&P). This appears to justify the initial categorization, and so, leads to active discrimination (R). People may respond to active discrimination by retaliating in a hierarchy where they have greater power. This can take the form of violence (S).

Tackling Discrimination

Tackling discrimination requires an understanding of its causes. Firstly, prejudice is inevitable. None of us can avoid it and it is futile to attempt to eliminate it. However, we should understand why it exists and how to prevent it from leading to discrimination. Education and our upbringing have a critical role to play in this.

We should also question our assumptions about the threats and opportunities associated with the categories into which we place people, especially if those assumptions have been received from others. Are the assumptions true? The best way to find out is to interact on common ground with people in that category. Generally, we will find the assumptions to be false, or to be a reaction to discrimination that they have already experienced. We should also ask ourselves “what is the source of these assumptions? Who benefits from them and how?”. Often, it will be found that they have been deliberately exaggerated to satisfy some political, financial, or economic need.

Active discrimination is clearly unethical. It can lead to conflict, thereby causing harm to both parties and to bystanders. It is an utter waste of the effort and of the resources that might otherwise go into improving the lives of all affected. There is a strong case for legislation to make active discrimination illegal, therefore, and for calling it out whenever it is encountered. However, education on the subject is also important. This is now accepted by many nations, but a few do not treat it sufficiently seriously.

There is much evidence that passive discrimination can ultimately erupt into civil dissent, causing active discrimination, and thus, have the same impact on society. Initially, however, it can slip under the radar. It is less obvious, and so, we are less aware of it. If we do become aware of it, then it is more readily deniable. Finally, it is difficult not to behave in a passively discriminatory manner or even to be aware that we are. This is because to do otherwise may conflict with deeply and unconsciously held beliefs about people. So, recognising and questioning those beliefs is important. However, solutions tend to be cultural ones. This is because it is the aggregate of individual passive discrimination that results in harm. So, civic education and awareness have important roles to play.

Where discrimination exists, the damage can be repaired by: encouraging interaction on common ground, i.e., in an arena where values and beliefs do not conflict; by emphasising the benefits of co-operative interaction; and by encouraging this to take place at whatever pace permits the steady reconciliation of differences. However, any disbenefits of co-operative interaction should not be ignored, but rather mitigated.