The Problem

From the results of a 2014 survey (McManus et al. 2016), the Mental Health charity MIND says that 1 in 6 people in England report experiencing a common mental health problem in any given week. These problems comprise:

- mixed anxiety and depression, 8 in 100 people;

- generalised anxiety disorder, 6 in 100 people;

- post-traumatic stress disorder, 4 in 100 people; and

- depression, 3 in 100 people.

However, these statistics include only those aged over 16, living in private housing, and living in England.

Suicidal thoughts and self-harm are not mental health diagnoses. But they are related to mental health. Over the course of someone’s lifetime (McManus et al. 2016):

- 1 in 5 people have suicidal thoughts,

- 1 in 14 people self-harm, and

- 1 in 15 people attempt suicide.

Women are more likely to have suicidal thoughts and make suicide attempts than men (McManus et al. 2016). But men are 3 times more likely to take their own life than women (Samaritans, 2019).

Unfortunately, these numbers have been increasing. MIND also report the following.

- The number of people with common mental health problems went up by 20% between 1993 and 2014, in both men and women (McManus et al. 2016).

- People reporting self-harm went up by 62% between the years 2000 and 2014 (McManus et al. 2016).

- People reporting having had suicidal thoughts within the past year went up by 30% between the years 2000 and 2014 (McManus et al. 2016).

There is also evidence that some minority groups are more likely to suffer mental ill-health problems than others. For example:

- LGBTQIA+ people are between 2 and 3 times more likely than heterosexual people to report having a mental health problem in England (Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2015).

- 23% of Black or Black British people will experience a common mental health problem in any given week. This compares to 17% of White British people (McManus et al. 2016).

- 26% of young women aged between 16 and 24 years old report having a common mental health problem in any given week. This compares to 17% of adults. And this number has been going up (McManus et al. 2016).

- Around 40% of people in England who have overlapping problems including homelessness, substance misuse and contact with the criminal justice system in any given year also have a mental health problem. This is sometimes called facing ‘multiple disadvantage’. (Lankelly Chase Foundation, 2015). According to the BBC report at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-49317060, police in the UK have been dealing with ever more mental health incidents.

The MIND report can be found at https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/statistics-and-facts-about-mental-health/how-common-are-mental-health-problems/.

This rise in mental ill-health seems to be occurring particularly among the young. US statistics on hospital emergency department visits at https://www.aau.edu/research-scholarship/featured-research-topics/teens-young-adults-drive-increase-mental-health-er show a clear link between age group and a rise in the proportion of discharges with a mental ill-health diagnosis. The rise has been most severe among those aged 10 to 44 and least severe among those under 10 or over 64.

The Causes

The question is, of course, “what is causing this rise?”. Clearly, the disruption of COVID has had a recent impact. However, the rise was apparent long before 2020. Economic shocks, such as the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, have also played a part. However, I would argue that the main factors are functional differentiation, progressive changes in our economy and toxic workplace cultures. I will discuss the former in this part and the latter two in the next article.

Functional Differentiation

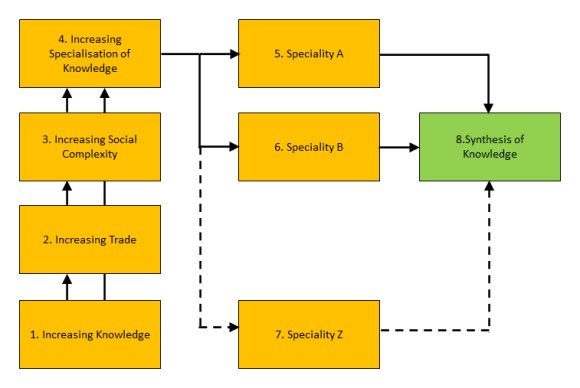

Functional differentiation is a steady and persistent growth in specialisation, and thus, in the complexity of society. Many economic shocks can be attributed to this trend.

Complexity is itself a cause of stress and anxiety as we struggle to understand the society that we live in. However, functional differentiation leads to an increasing number of interactions between individuals and organisations. It has also led to globalisation and an increasing number of interactions between national cultures. Finally, it leads to increasing migration and interactions between the minority and majority cultures of a nation.

These increasing interactions have resulted in an increased risk of conflicting values or beliefs. If the parties to an interaction select the option of holding firm to their conflicting values or beliefs, then there is a risk of negative competition and conflict, both of which are major causes of anxiety and depression. Alternatively, for the two parties to interact effectively, one or the other must wear a mask, i.e., hide their true values and beliefs and create an appearance of holding the same ones as the other. As Karl Rogers has pointed out, the effort of maintaining such a mask can lead to mental ill-health. So, whichever alternative the parties choose, there will be an impact on the mental health of at least one of them.

The fact that minorities are at greater risk of mental ill-health supports this argument. In their interactions with the majority culture, there is a greater risk of conflicting values or beliefs, and thus, they either face the risk of social conflict or must wear a mask. The recent rise in minority rights groups has meant less pressure for minorities to do the latter. However, it has transferred the pressure to wear a mask to members of the majority. Where neither party is willing to hide their true values and beliefs, there is also a greater risk of conflict.

The rise in mental ill-health amongst the young is often attributed to smartphones and social media. However, these technologies are a product of functional differentiation, as well as probably also contributing to it. Smartphones and social media increase the number of interpersonal interactions, and thus, the potential for conflicting values or beliefs.

In summary therefore, functional differentiation leads to increasing social complexity and an increasing number and diversity of social interactions. The increasing number of social interactions leads to an increasing risk of conflicting values or beliefs. The increasing risk of conflicting values or beliefs, no matter how we deal with it, leads to an increasing risk of mental ill-health.

References

Journal of General Internal Medicine (2015), Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey.

Lankelly Chase Foundation (2015) Hard Edges: Mapping severe and multiple disadvantage.

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. (eds.) (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014.

Samaritans (2019), Samaritans Suicide Statistics Report.