Introduction

This article proposes a single deep conceptual framework that unifies many of the concepts of systems theory, such as systems, holons, holism, relationships, emergence, causality, isomorphisms, etc. This framework may form the basis of a general system theory. Some of its definitions may seem obvious, but I have included them for the avoidance of doubt and to paint a complete picture.

Conceptual Frameworks

There are two ways to define a word. The first is by reference to observed reality. For example, we can all agree on the definition of the word “snake” because we can observe a snake in the external physical world. However, there is less agreement over more abstract words such as “justice” and “conflict”. This is because we are unable to observe all instances of those concepts. To overcome the latter problem, we attempt to define the word, but in doing so, we must use other words.

A conceptual framework is essentially a set of definitions of more abstract words that is internally consistent and founded on axiomatic words, i.e., words that are not defined and are taken as being self-evident. A conceptual framework comprises our understanding of the words and the universe that they represent. We all hold conceptual frameworks. However, they vary greatly in their depth and nature. The deeper a framework, the more fundamental and general the words it defines. For example, the word “relationship” is deep and has broad application, whilst “unhappiness” is far less so, applying only to human beings and some animals in a particular state.

The development of any theory first requires a conceptual framework. To use an analogy from physics, the absence of a framework is equivalent to attempting to build a structure with gas. On the other hand, if we do have a framework, then we are building with a solid. Furthermore, if more than one person is developing a theory, they will need to agree a single framework if they are to communicate successfully. It is OK to consider different perspectives, but ultimately, they must be drawn together into a single consistent whole. In the case of general system theory, we are attempting to develop a very general theory indeed. So, we need to ensure that the framework is as deep as we can make it.

The absence of a common framework can be seen on the internet. Authors do have their own conceptual frameworks of course, but rarely are they explained, and their number can be overwhelming. Furthermore, there is clearly competition between them for more general acceptance. So, the motives of their proponents must also be questioned. Finally, their depth is rarely great, and so, the theories that they underpin can be quite specific rather than general. To unify these frameworks, much effort would be required in drawing them together and analysing them for a deeper one that applies to most.

Cognitive Physicalist Philosophy

My proposed deep framework is founded on Cognitive Physicalist philosophy. The physicalist aspect of this philosophy holds that everything, including objects, abstract concepts, and information, is physical in nature and occupies a region or regions of space-time. The cognitive aspect recognises that human beings have limited perception and cognition. Because the universe of space-time is probably infinite, to understand and explain it we must simplify it. So, physicalism enables us to establish a single conceptual framework, but cognition limits our understanding and perception.

Spiritualism

Many people believe that there is also a spiritual aspect to nature, and so, reject physicalism. However, the source of our spiritual beliefs is probably an unconscious sense that we use emotion in our decision-making processes. It is certainly true that we rely heavily on the unconscious mind and on emotion when making our decisions. This is something that we have inherited from simpler organisms and that evolution has built upon. In the absence of a rational scientific explanation for the process, it can take on a mystical flavour, and can seem to be an alternative to our other skill, conscious rationality. In practice, from an evolutionary perspective, emotion-based decision-making is entirely reasonable, and the emotional and rational aspects of our minds work hand-in-hand to our benefit.

The Importance of true axioms

Over 25 years ago, I became very frustrated with conventional symbolic logic. It comprises numerous disparate branches and a plethora of different symbolisms that create much confusion. So, I embarked on a project to join up the various branches using a single common symbolism. Not only was I successful in unifying these branches, but also in including both natural language and mathematics. However, what was originally intended to be a five-year project turned out to be a twenty-three year one.

There were two main outputs from this project of significance for systems theory. Firstly, part of the project involved the axiomatization of logic, i.e. the identification of a number of self-evident but unprovable truths on which all of the remaining theory can be based. It was necessary that these axioms provide an explanation for all generally accepted laws of logic. As I unified the different branches, I found that many of the axioms for a traditional branch of logic, and indeed mathematics, were in fact theorems that could be derived from deeper and more general axioms. Nevertheless, a small number always remained that were particular to a branch and distinguished it from the others.

Secondly, physicalism was the only approach that would provide a single framework. Symbolic logic is almost self-defining. All its theorems arise from the operations of its axioms on themselves. The one and only axiom that might be regarded as not being of logic is the physicalist one.

These concepts can be used when considering a general system theory. Providing they have an empirical basis in reality, two ideas can be likened to two minor branches of a tree. If we are aware only of the branches but not the tree, then the two ideas may appear to contradict one another. However, if we can identify common truths from which both ideas can be explained, then we have identified the larger branch from which the minor ones sprout. That is, we are beginning to perceive the tree. In this analogy the common truths are, temporarily at least, the equivalent of axioms. This process can continue until we reach the trunk of the tree. The more ideas we are able to join up in this way the more likely their common explanation or axiom is to be true.

The truth of an axiom is not guaranteed of course. Many times, I have had to revise axioms that have proven inconsistent with other branches of logic. So, a certain amount of objectivity and persistence is needed. Furthermore, there is no certainty that the tree does ultimately have a trunk, i.e., that there are universal axioms. Bearing this in mind, together with the fact that some axioms are particular to a branch, i.e., are emergent, it seems unlikely that there is a single simple explanation for everything. Nevertheless, we can attempt to find one for those few things that lie within human experience, and this is what my proposed framework attempts to do.

The remainder of this article now describes the framework.

Information

According to physicalism, information is physical in nature. It also appears to be something that only living things and some of our artifacts are capable of recognizing and manipulating. The term information at source refers to the structure of a physical entity. When we see other things with a similar structure we recognise them, i.e., create a mental image of them, for future reference. We also give them a name so that we can pass our knowledge of those things to others. Thus, the original information is translated and communicated. Nevertheless, all of those translations and communications are physical in nature. A mental image is an arrangement of neurons and the way that they fire; speech comprises patterns of vibration in air; and so on.

However, our perception and information processing abilities are limited. So, in translating and communicating we simplify; we assume; we make mistakes; we reject or modify new information that is not consistent with our existing knowledge; and so on. Thus, information can be false.

Holons

Arthur Koestler originally described a holon as being any entity that can be recognised as a whole in itself and which constitutes part of a larger whole. However, for the purpose of this framework, a holon is also an entity that comprises a collection of other holons with relationships between them. Every holon is a system with inputs, processes, and outputs. It is also physical in nature. These definitions are true not only of physical objects, but also, of events and more “abstract” concepts such as justice, conflict, etc. For example, justice is the set of all just acts.

Holism

The term holism refers to a system having properties that its component parts do not, that is, emergent properties. For the purpose of this framework, a holon is further defined as being something at which a new property first emerges as the complexity of entities increases. Thus, all holons have emergent properties and are holistic.

Relationships

A relationship between two things comprises those things for so long as they are related to one another in a particular way. It also includes whatever is transferred either way in that relationship, whether it be space, matter, raw energy, or information.

Every relationship also has outputs. At least one of these is its appearance, i.e., its information at source. There is a question over whether this appearance is an emergent property, i.e., a property that the relationship has, but that its component parts do not. If so, then all relationships are holons because they have emergent properties. If not, then a relationship is not a holon. For this article I will assume the latter, i.e., that the appearance of an entity is not an emergent property. However, it should be borne in mind that this is an assumption and not necessarily true.

Complexity

The complexity of a relationship or holon can be measured by the number of fundamental particles that it comprises. For the present, at least, we can regard fundamental particles as those identified in the Standard Model of physics.

The more fundamental particles an entity comprises, the more variability there is between entities in the same set. This is because we form sets based on the similarities that we observe between entities. It is a human cognitive act, and we are limited in the amount of complexity that we can manage. To address this variability we create prototypes, i.e., mental images of a typical member of the set that has only the characteristics we have used to define the set, and none of the variability.

Holon Formation & Chaos

There must be a certain number of relationships between holons before a higher level holon is formed, i.e., before an emergent property other than appearance is encountered. This emergent property can be an output from the holon which in turn can be the basis for relationships between higher level holons.

Between the formation of holons at one level and those at another, the number of relationships increases and may exceed the threshold of our comprehension, thus appearing chaotic.

Abstract Entities

Every relationship or holon is part of a set of similar ones, and this set is itself a relationship or holon. However, because it comprises components that occupy several separate regions of space-time, the set may not be observable in its entirety. This is reflected in natural language. For example, “conflict” comprises several instances of conflict, each of which is “a conflict”. We can perceive several instances of conflict but not “conflict” in its entirety, and so, we may label it an abstract concept. Nevertheless, it is real and physical.

Despite being collected together into a set on the basis of common features, the individual holons or relationships may also have features that are unique to themselves. This presents a communication problem. Each observer, a diplomat and a family counselor, say, will observe a different subset of conflicts, and so, will form a different understanding of the concept. So, when one is discussing the topic with the other misunderstandings are almost inevitable. Worse yet, different observers can give different names to the same thing in different contexts. This can make communication between the two difficult, if not impossible. It can also obscure the fact that they are discussing the same concept.

Causality

Holons or systems have outputs that act as inputs for other holons or systems. This is the same as causality and is reflected in our use of natural language. For example, “conflict” may cause “poverty”, and “a conflict” may cause “an instance of poverty”. It is what is exchanged between the two holons or systems that provides the causal link. Their processes and outputs are causes; their inputs and processes are effects. This transfer is evidenced by the fact that causality cannot propagate at greater than the speed of light. As Hume observed, a cause must be spatially contiguous to its effect and must precede it.

The normal laws of causality apply to these relationships. That is, a cause may be necessary or sufficient for an effect. Also, several necessary causes may only together be sufficient.

One thing that is often overlooked in causality is the existence of inhibitors. That is, those things that prevent an effect. Again, inhibitors can be necessary or sufficient to prevent an effect. Also, several necessary inhibitors can only together be sufficient to prevent it. This is of importance when it comes to the discussion of living entities, holons, or systems.

Function & Purpose

The function of a holon or system can be regarded as its outputs. However, because these outputs are inputs for other holons or systems, i.e., effects, these effects can also be regarded as the holon or system’s function. The purpose of a non-living entity is the same as its function. However, a living entity with agency can regard its purpose as being what it would like its function to be.

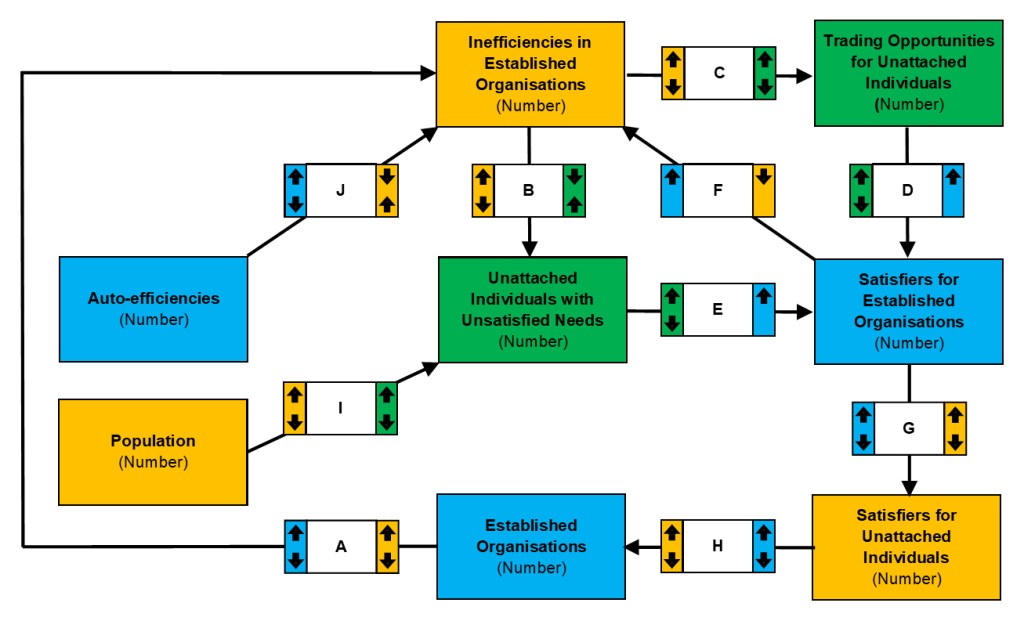

Needs, Satisfiers and Contra-satisfiers

We use different language when referring to living entities, systems or holons. The needs of a living entity are the equivalent of its function. If those needs are not satisfied the entity fails to function. For example, if we lack oxygen we die. The same is true of some of our artifacts. If a factory lacks electricity it ceases to operate. The inputs to living entities and some of our artifacts are satisfiers or contra-satisfiers. A satisfier is something that increases or sustains the level of satisfaction of a living holon or system’s needs or that of an artifact. It is also a necessary cause of the system’s function. A contra-satisfier is something that reduces the level of satisfaction of a system’s needs. In other words, it is an inhibitor.

Isomorphisms

Isomorphic entities are instances of the same set of holons or relationships. That is, entities that have the same arrangement of components and the same causal relationships between them. They can be difficult to recognise because different people observe different subsets of the set, and so, form different understandings of it, and use different words to describe it. To refer to an earlier analogy, isomorphic entities are different minor branches of the same tree. They can only be identified by discovering the same branch from which they sprout.

It is not necessary to use mathematics to identify isomorphisms. Rather a comparison of their function, outputs, and the causal relationships between their components can achieve the same result. It can be challenging, however, to identify what is passed from one holon to another in a causal relationship.

To cite the example of conflict causing poverty, this is in fact an indirect causal relationship brought about by the agents of conflict competing with the impoverished for limited resources. The resulting shortages then act as a contra-satisfier for the latter.

To some extent the difficulties in identifying isomorphisms can be overcome by poly-perspectivism, i.e., understanding the language and opinions of others and seeking a common explanation for those apparently divergent views.