Networks are a feature of living things and some of the artificial things that they create. Individual people, organisations, and the relationships between them form a network known as a “social network”. Unfortunately, however, this term is now popularly understood as referring to social media on the internet. The term also tends to imply interactions involving the exchange of information. Strictly however, a social network can be between not only individuals but also between organisations of any size. Furthermore, the relationships involve not only the exchange of information, but also the transfer of energy, materials, money or any other satisfier or contra-satisfier. This usually takes place in the form of a two-way trade.

It is worth mentioning at this point that not all social networks are desirable. They can, for example, be criminal or drugs networks. They can also comprise self-interested individuals or organisations with influence over politicians.

Historically, the factors that have governed whether there is a relationship between two people, or two organisations have been:

- geographical, i.e., whether geographical proximity and other factors such as trade routes have enabled communication and the exchange of satisfiers or contra-satisfiers; and

- whether the level of disagreement has permitted co-operation, has resulted in negative competition, or has resulted in an unwillingness to interact.

With the advent of the internet and globalization, geographical factors have become less of an obstacle.

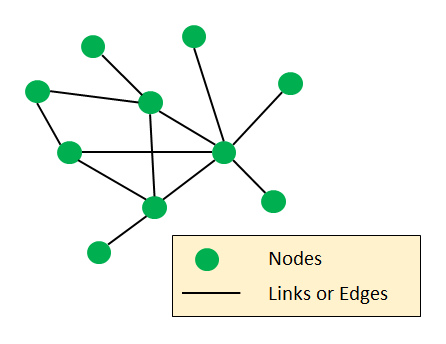

The analysis of a social network is carried out using a diagram. Individuals or organisations are plotted as nodes, and the relationships between them are plotted as links. The latter are also sometimes referred to as edges. Software and statistical techniques are available to optimize such diagrams, but little is available to carry out further analysis and, for example, make predictions. For the present therefore, analysis is largely a process of visually inspecting the diagrams.

From them, it can be possible to identify the following.

Communities or clusters have a greater number of internal connections than external ones. People or organisations are attracted to one another if they can co-operate. In this way they form clusters. Examples are intra-organisational networks, that is, networks within an organisation. They can be formal or informal. Formal internal networks are often both functional and hierarchical because this aids our understanding of them. Informal networks are less so. From the diagrams it can be possible to identify both intra-organisational and inter-organisational informal networks that might otherwise be invisible. Such informal networks are organisations in their own right, and can act as holons in a simpler model. Communities or clusters tend to have a relatively homogenous culture, i.e., the same shared values and beliefs. Internal interactions reinforce their paradigms and worldviews and can cause them to become entrenched. External contact with conflicting worldviews, especially those that pose a threat, can lead to further reinforcement.

Structural holes occur when there are relatively few connections between two communities or clusters. They can be caused by geography or other difficulties in communication. Also, they are often a result of two communities or clusters having too great a difference in their values or beliefs. However, if two clusters can interact because their differences are not too great, then both may benefit.

Marissa King, professor of organizational management at Yale University, describes, in her 2021 book “Social Chemistry”, three different ways in which people approach social networking. Although these ways are particular to social media on the internet, they are also of more general application. They are as follows.

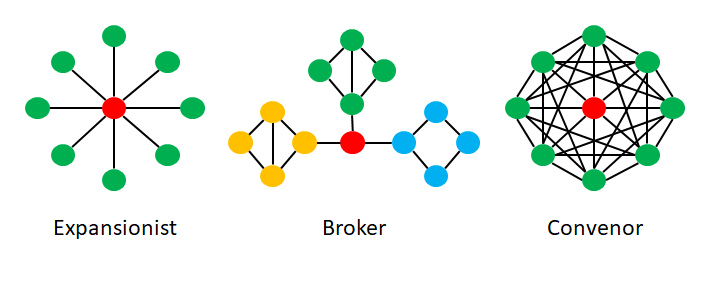

Expansionists have large networks with many connections. In more general networks, the node that they form is referred to as a hub. Managers and leaders form hubs in formal organisations. As is well known in the advertising industry, hubs are a useful tool for quickly disseminating information to a community. However, according to the anthropologist, Robin Dunbar, there is an upper limit of 150 on the number of social connections that an individual can maintain.

Brokers bring together people from different communities. They act as a bridge over structural holes and can act as intermediaries when there is disagreement. As mentioned in the previous article, if such disagreement is not too great, then the communities can achieve a consensus that may be of benefit to both. Thus, brokers can be creators of value.

Convenors build dense networks with many interconnections. For this to be possible common values and beliefs must be shared, and a convenor is instrumental in this. Shared values and beliefs enable greater co-operation. However, they also make a community more resistant to change, and so, structural holes are more likely to form around it.

Individuals or organisations who fulfil these roles can also be identified from a network diagram, as demonstrated below.

However, social network diagrams do not describe the nature of the information, energy or material that is being transferred from one node to the other. Nor do they describe the effect of any changes to these transfers on the recipient. To fully represent a network of interacting organisations it is therefore necessary to describe the links in more detail. A way of doing so is described in the articles that follow. The result is a causal network diagram.