Organisations are recursive, i.e., within any organisation there are component organisations. The same is true of the command and subordinate components of an organisation. Thus, within any command component or any subordinate component there are lesser command and subordinate components. This recursion continues until we arrive at a single individual, and so, every organisation is structured hierarchically. When an individual is a command component they are referred to as a leader. When a subordinate component, they are referred to as a follower. In practice, hierarchies exist throughout human society, and all but a very few individuals are both leader and follower. Thus, when a command is given to a subordinate component it is the command component of that subordinate component, and ultimately an individual, who is responsible for implementing it.

Both the follower and the leader have a complex of needs, and each is looking to the other to help satisfy them. Thus, the leader / follower relationship is negotiated and, if successful, provides emotional benefits to both parties. Some individuals, however, have higher followership tendencies than others. This depends on their genetic inheritance, upbringing, education, and experience. The relative influence of each factor varies from individual to individual. In practice, an understanding of human society is beyond our individual cognitive ability, and so we often simplify. Simplification can involve following a trusted leader, or following a trusted ideology, philosophy, or religion. A high follower tendency can be due to low cognitive skills, or training such as that in an army or domestic service. It can also be due to a high level of trust in the leader, gained from experience or by feedback from one’s peer group. If satisfiers have been identified and exchanged between the follower and the leader to the satisfaction of both, then mutual trust also develops.

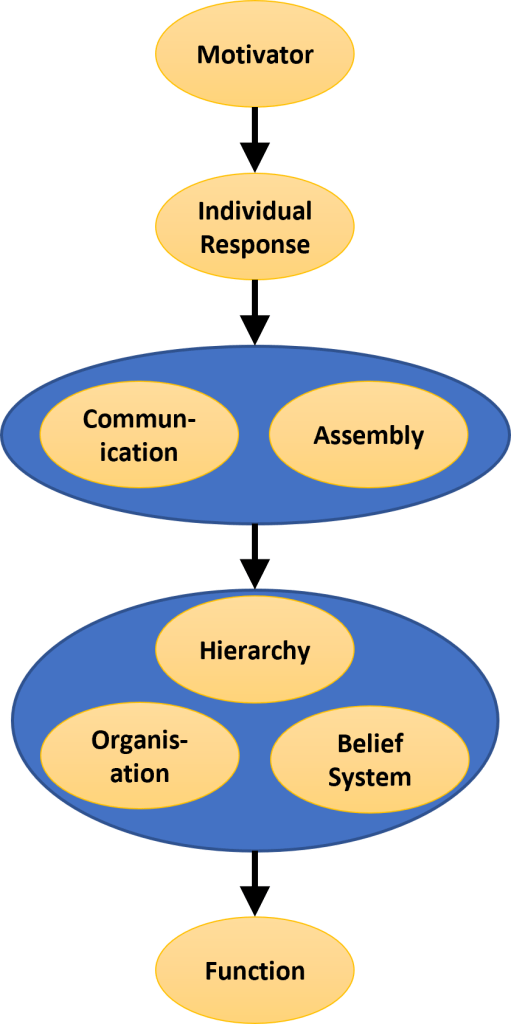

If an individual has a high follower tendency, then they will unquestioningly implement commands. However, if they do not, then the process is as follows.

To incentivise the follower, the leader will have offered motivators in return for carrying out their command, or will have threatened motivators in return for not doing so. However, it is the follower’s interpretation of these motivators that is important. Errors can arise in communicating the leader’s offer and, normally, offers of reward are latent, i.e., deferred until completion of the task. These facts can be deliberately exploited by the leader as a rationale for not fulfilling their promise, but this does, of course, diminish the follower’s trust.

To attract followers, the leader will also have displayed a willingness and ability to provide such motivators. The more the follower trusts the leader, the more he will believe these displays. On the other hand, the more he distrusts the leader, the less he will believe them.

If the leader’s motives for issuing the command are self-serving or culturally non-compliant, then he will attempt mitigation strategies. These take the form of false displays of culturally acceptable motivation, explanations, rationales, distractions, etc. They are criticised by the follower and either believed or not. If the follower trusts the leader, then he is more likely to believe them. The follower then compares his beliefs about the command for compliance with the culture in which the organisation operates. For this to be possible the follower must have a cultural schema and an accurate knowledge of that culture.

The more the follower role is wanted, the greater the follower displays their willingness and ability to co-operate. This can take the form of voluntary feedback and displays of support for the leader. The type of leader that people choose to follow depends on the prevailing circumstances, i.e., whether we face an existential threat, a non-existential threat, or there is a period of stability. On the other hand, the less the follower role is wanted, the more they will avoid making such displays, and the more they will avoid placing themselves in a position to receive such commands.

The follower interprets the leader’s command, instruction, request, or implied wish. Such commands can have a positive or negative emotional impact. They are positive if they happen to coincide with action needed to provide the follower with personal satisfiers. Mostly, however, they are negative, require personal effort to implement, and yield no benefit other than positive feedback to the leader.

The promise of reward has a positive emotional impact on the follower. Its magnitude will depend on the relative priority of the follower’s needs at the time. However, the more the follower believes the leader has the will and ability to provide the motivator, the greater the overall benefit. Providing there is an overall benefit, the follower will seek to acquire these rewards by carrying out the leader’s commands. The more the follower benefits in this way, the more he will wish to remain a follower.

Threats of punishment, on the other hand, have a negative emotional impact. The follower will seek to remove them, either by carrying out the leader’s command or, if possible, by ceasing to be a follower. The greater the follower’s belief in the willingness and ability of the leader to implement such threats, and the greater the net disbenefits of following the leader’s commands, the less willing he will be to continue as a follower.

The follower uses a form of emotion-based risk/benefit/cost analysis to assess the overall impact of carrying out the leader’s command, taking the following into account:

- The greater the positive emotional impact of acquiring the promised motivators or of avoiding the threatened motivators, the greater the overall benefits.

- The greater the follower’s belief in the willingness and ability of the leader to provide those motivators, the greater the overall benefits.

- The more the resources available to the follower, and the fewer needed to implement the command, the greater the overall benefits.

- The nature of the follower’s peer group also has a part to play. The more compliant it is with the wishes of the leader, the greater the overall benefits.

- If the follower accepts that the leader’s motives for issuing the instruction are culturally compliant, this will increase the overall benefits. If the follower does not, then due to the risk of social censure, this will decrease the overall benefits.

- Finally, any other risks are taken into account.

A decision is then made based on this analysis. If a course of action has a positive overall emotional benefit, then the command will normally be implemented. If it has a negative one, then it will not. If implementation does not comply with cultural values and norms, then mitigation, in a form borrowed from the leader, will be necessary. The resources required will have been taken into account in the risk/benefit/cost analysis.

The consequences of implementing or not implementing a leader’s command depend on the nature of the command. Clearly, if it is harmful from a utilitarian perspective, then there are benefits to the organisation’s stakeholders in not carrying it out. Not all self-serving or culturally non-compliant commands are harmful in this way, and so these in themselves are not criteria for failing to implement a command. Rather, difficulties arise due to blind followership, a lack of criticism of the leader’s mitigation strategies, and failure to understand the culture and the ethics that underpin its values and norms. Almost without exception, we all have a follower role and a significant part to play in constraining a leader’s excesses. We should therefore treat the role seriously, and develop appropriate skills.