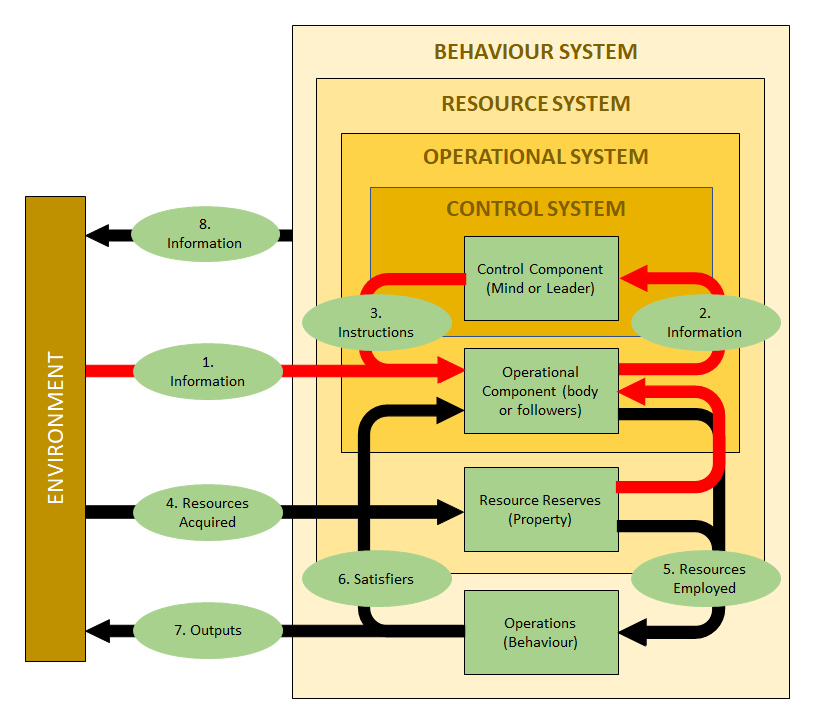

Human behaviour, whether that of an individual or that of a larger organisation, is a process. So, together with its inputs and outputs, it can be regarded as a system. The diagram below describes this system.

The behaviour system is part of a nested hierarchy comprising other systems. They are arranged as follows. The control component, in the case of an individual, is his mind, and in the case of a larger organisation, its leader. Together, the mental and physical resources that they directly control, i.e., the body of an individual or the people in a larger organisation, comprise the operational system. The operational system, together with the resources that it owns, comprise the resource system. Finally, the behaviour system comprises the resource system plus actual behaviour.

These systems operate in the following way. Paragraph numbers refer to those in the diagram.

- The environment comprises everything that is not a part of the system. It includes both the natural and the social environments. Inputs from the environment enter via the operational component. These inputs include risks and opportunities. The relevant parts of the operational component are, in the case of an individual, his physical senses, or in the case of a larger organisation particular individuals. For example, an individual may perceive a wasp as a threat of injury, or a government may see another nation as an opportunity for trade.

- Information from the environment is passed from the operational component to the control component, i.e., the mind or leader, where decisions are made. The operational component monitors the state of resources and satisfiers, i.e., those things that satisfy the individual or organisation’s needs. It also passes this information to the control component. For example, an individual may recognise that food in the refrigerator is running low, or a business that its stock of spare parts is too high.

- In return for this information, the control component makes decisions, and then, passes instructions to the operational component. These instructions are based on a risk, cost, benefit analysis that uses the value of satisfiers or contra-satisfiers and the resources required to create them. The value allocated to a satisfier or contra-satisfier depends on the interaction style of the individual or leader, i.e., whether they are co-operative, positively competitive, or negatively competitive. A negatively competitive individual may conclude that shoplifting is the way to fill their refrigerator. A government with a co-operative style may see a trading alliance as the way to improve their economy.

- Resources are acquired from the environment and become part of the resource reserves of the system, i.e., its property. They can be matter, energy or money. Resources can be acquired directly from the natural environment, or through trade with other individuals or organisations. Early humans were hunter-gatherers and acquired their food directly from nature. Today, however, many of us buy our bread from a baker or supermarket.

- The activities of the operational component, together with resources taken from reserves, act as inputs to the operations process. These inputs are satisfiers for the process. The operations process converts these resources into outputs. So, for example, an individual may cook the food in their refrigerator to create a meal. A business may assemble parts, or mix constituents, to create a sellable product.

- Some of these outputs are satisfiers for the operational component. We may, for example, eat part of the meal we have prepared to satisfy our personal need for sustenance. Similarly, governments and businesses pay the people who carry out their function.

- Other outputs can be satisfiers or contra-satisfiers that are used to trade for resources from other individuals or organisations. So, we may trade our labour for pay or provide a meal to friends in return for their friendship. Businesses do, of course, provide goods and services in return for payment. Alternatively, outputs can be operations on the natural environment to acquire resources, e.g., mining, hunting, or gathering. All behavioural outputs are constrained by the physical resources available, for example, an individual’s physical abilities. They are also constrained by the operational resources owned, for example, the financial capital of a business.

- Finally, behaviour can be observed, and so, the system of which it is a part outputs information to the environment. We can, for example, watch a football match or observe government activities, and thus, criticise them.

Organisations are recursive. Every organisation comprises several lesser ones. Every organisation, together with others, is also part of a larger one. This recursion continues downwards to individuals and upwards to all of humanity. This model describes the behaviour of every individual or organisation in that structure. So, it may provide the basis for a systems psychology of both individuals and organisations. Notably, it provides a basis for social learning theory which postulates that we emulate role models, that our behaviour is reinforced by the approval of others, i.e., satisfiers, and extinguished by their disapproval, i.e., contra-satisfiers.

The model may also be a basis for dynamic models of society, thereby enabling predictions to be made.